Welcome to dear midnight, my bi-weekly newsletter with reflections on all things photography, publishing and the artistic process.

In this space I write about the material that inspires me, both for my own art practice and Foam Magazine, a biannual publication that looks at universal themes through the medium of photography. Thank you for subscribing, I hope you will feel inspired!

Overstimulated but hungry for more, I managed to make my way to London last weekend for the yearly indulgences around Offprint, Peckham 24 and Photo London. Driven by the unquenchable wish to see it all I sketched out my itinerary beforehand and, as usual, was extremely thankful to have been set off my ambitious track by the many lovely encounters and distractions that were waiting for me along the way. One of those detours led me to join an intimate tour of the V&A’s Fragile Beauty: Photographs from the Sir Elton John and David Furnish Collection - a show I wouldn’t have sought out personally, but which presented me with the rare chance to meet face-to-face an artwork that had occupied my mind for the past months.

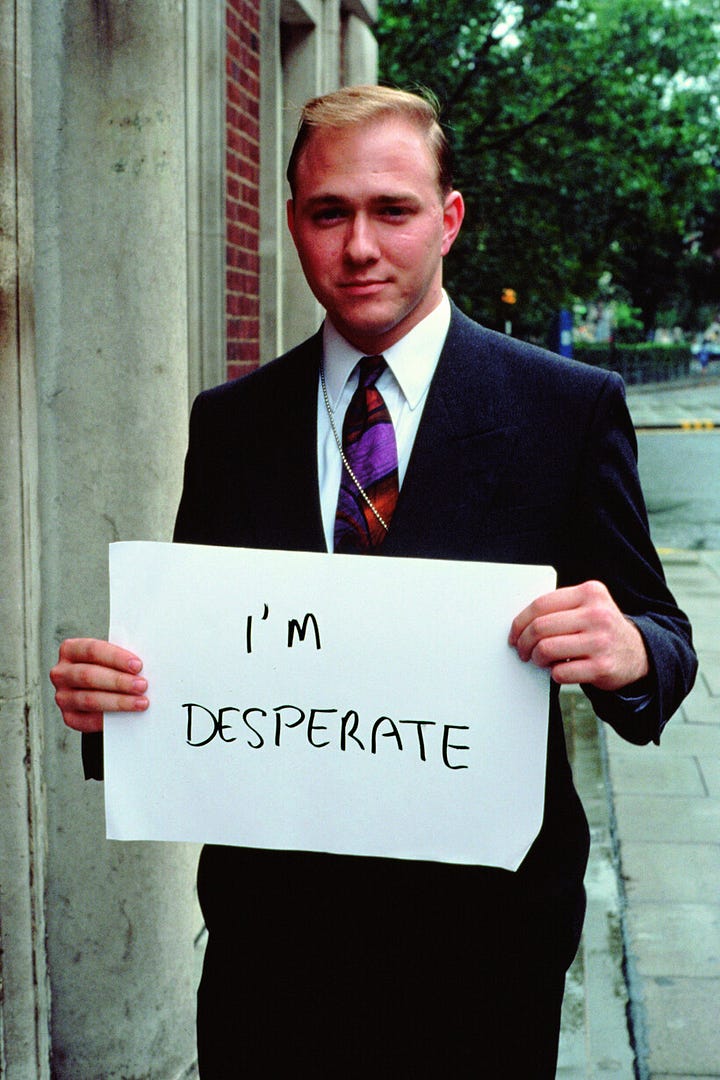

British artist Gillian Wearing has photographed other people for most of her career attempting to capture the psychological depths that might usually remain hidden. In her series Signs that say what you want them to say and not Signs that say what someone else wants you to say (1992–1993), Wearing asked strangers on London’s busy streets to take a moment to write down their thoughts and opinions on white cardboard. She then photographed them holding their signs, revealing the disconnect that exists within people’s personal and inner selves versus their public personas - what they show to the rest of the world.

In recent years, Wearing has turned the camera upon herself — if one can call it that. Peering through surprisingly convincing masquerades, she slips in and out of characters, adopting bodies and personas that mislead us into believing that what we are seeing is the real Gillian Wearing. As viewers, we are confronted with an enigma that hides behind masks to speak about the performative nature of identity. While engaging with her images, one experiences the uncanny feeling of looking at a shell. We recognise the image, in most cases even the person, but something seems off. After closer observation, we might notice that Claude Cahun, Diane Arbus, and Weegee are looking at us through the same eyes; that there is someone beyond the surface, inhabiting their image. And it is exactly this body of work that I included in the theme text for the upcoming issue of Foam Magazine Missing Mirror - Photography through the lens of AI.

In her work Wearing blurs the lines between truth and adaptation to an extent that makes you doubt your own ability to recognise human traits. It makes you look twice, and search more diligently for recognisable traces of humanness — a skill we will need to hone in the future. In Foam Magazine #46, we showcased works that deal with questions about Who We Are. Almost ten years on, the integration of AI into every level of our lives prompts the question who are we in the face of AI? Which of course leads to the most obvious one: Who is AI?

1: Artificial Intelligence

Are you a robot? is a question everyone has likely come across while using the internet. The most common way to prove that you are, in fact, not a robot is by analysing a set of photographs and selecting the ones depicting a bus, a motorcycle, a fire hydrant, or a traffic light. With this simple but effective way, you demonstrate your ability to interpret images and automatically position yourself out with the capacities of traditional operating systems or viruses. Until now. The ability of machines to ‘see’ has improved tremendously over the past decades, meaning that computers have been trained, by humans, to recognise and generate images that come shockingly close to a photo. We recognise the need for a platform to understand the mechanics behind the technology, discuss how the photographic medium is influenced, and in which ways we need to adapt our reading and handling of images.

MISSING MIRROR - Photography through the lens of AI is a multidimensional project hosted by Foam, combining an exhibition, digital platform, and magazine. Together we look at the growing overlaps between art, technology, and society, exploring how the recent advancements in AI impact our relationship with the image, ourselves, and our perception of reality. How do we form a truthful image of the world when credibility is questioned? And vice versa, how do we recognise ourselves in the images around us?

Artificial Intelligence (AI) in its broadest sense, is intelligence exhibited by machines, particularly computer systems.

2: The Aleph

Our cover is adorned by an AI generated image from the series Aleph-2 by artist Juan Manuel Lara. Aleph-2 is a collection of images described in the short story The Aleph, by Jorge Luis Borges. In the story, Borges introduces the Aleph, a sphere that concentrates all the images of the universe and that grants the experience of the absolute to whoever approaches the eye and sees. Lara used a paragraph from the short story to create prompts for his images. Like a modern Aleph, artificial image-generators grant the wish to shape all that can be named, on demand and in the moment.

KH: When did you first come across the short story The Aleph? What was your first impression?

JML: I came across the story not long ago, approximately two years. In fact, I already knew it because it is a classic, but I read it two years ago while I was doing my first tests with images made with AI. What I remember is that the paragraph that I finally ended up working with in Aleph-2 stayed with me quite a bit because its images are very striking. I had it in mind when I started rehearsing with Dall E 2, which is the program that I used to make Aleph-2, so I wanted to combine those two worlds.

KH: How would you describe your relationship with AI throughout the process of making this work?

JML: At first this link arose from the fascination generated in me by the fact of being able to write something and receive images in return, with astonishing speed and also with technical characteristics that closely resemble photographs, as we know them. And then that possibility of obtaining images almost automatically and having a certain correlation between the text and the image, or seeing how this game between text and image worked, fascinated me a lot to the point of making hundreds or thousands of images, which was a little the work process to get to this series.

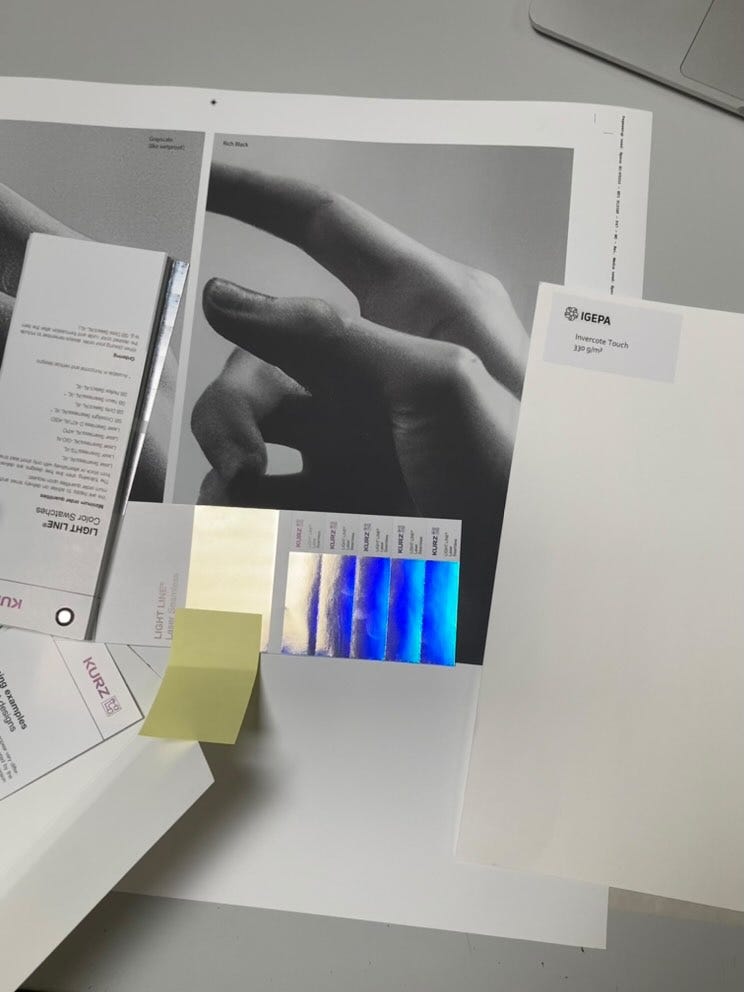

KH: Can you tell us the story behind the image on the cover of Foam Magazine?

JML: The passage from The Aleph that I used for that image speaks of the ‘delicate bone structure of a hand.’ And as a result, many images were generated, but I like this one in particular because the motif of the hand pointing upward is repeated quite a bit throughout the history of art and in this case the particularity is that it has four fingers. At first glance it may not be noticeable, but if you look closely it is, and I think that gives this image its particular characteristic. It not only brings together this classic motif such as the hand pointing upwards towards the sky, but also the very characteristic of this generative technology, which is the representation of hands in a very problematic way, very deformed or with les or more fingers. So in addition to being a very beautiful image, it brings together several meanings that are very powerful for me.

KH: Agreed!

KH: The book has a very unique paper and printing quality! How did you approach the translation of AI images to printed publication?

JML: The Aleph-2 project first emerged as a game, but later it arose with the idea of publishing a book. We worked on it very closely with Martín Bollati, who is the editor of this book (SED Editorial) and from the beginning there was the idea of printing it in black and white and with the risograph technique, which accentuated certain characteristics of the images that I was realising: the grain placed in the foreground, the play of light and contrast. And that had a lot of influence on the final result that we ended up editing.

KH: What do you think is the impact of AI on image production? And how do you see it unfolding in the future?

JML: It seems to me that we are all guessing what the impact is, based on what we are experiencing at speed, so I am not very clear about the answer. What I do believe is that in the near future a classic photo and one generated by AI will be indistinguishable (in some cases it already is), so those separations will be erased. Ultimately it will also affect the character of truth or what is true, we will ask ourselves why something is true and where reality is most, if in the place where we always believed it was or is it going to be something even more diffuse and abstract from what it is now.

3: Artistic positions

Taking into account that things are still very much ‘in progress’ the magazine hosts a series of conversations between thought-makers and pioneers in the industry, like Hito Steyerl, Fred Ritchin and Giselle Beiguelman, who chew on the most relevant ethical questions concerning AI, covering topics like credibility, copyright, bias, post-truth, fake news, and more.

The portfolios present a wide range of artists who engage in one way or another with digital realities. Politics of memory, identity, gaze, science fiction and creation permeate the pages of this issue with works that we hope help to unfold the theme but also show new facets to our understanding of what AI can do and look like. Alongside the images we publish especially commissioned texts that contextualise the works and elaborate on the central themes and questions. A few examples:

‘In Another Online Pervert, artist Brea Souders invites us into a deeply personal, year-long dialogue with a conversational chatbot. Out of curiosity, Souders started chatting with an artificial intelligence: female, programmed by men, perpetually eighteen, knows 350,000 words, favourite colour: blue. Underneath the often funny — slightly uncanny — chats between the two, lies the artist’s profound interest in differing perceptions of time, other life forms, and exploring personal meaning in our increasingly AI-mediated world.’ - Winke Wiegersma

‘For much of South Asian history, the division of public spaces along caste lines has been a consistent fact. In kingdoms where the Manusmriti was adhered to as law (something that was rather common as recently as the late 19th century), it was explicitly forbidden for Dalit bodies to pass through the ‘main village’ lest our presence pollutes the sanctity of Hindu life. (..)The death rituals that Kumaraswamy invokes through his work [marana, demise] are the only eschatological leeway for our bodies to use ‘public space’, and in turn, in death, the Dalit body approaches the fleeting formation of a counter-public and reclamation of the streets.’ - Rahee Punyashloka

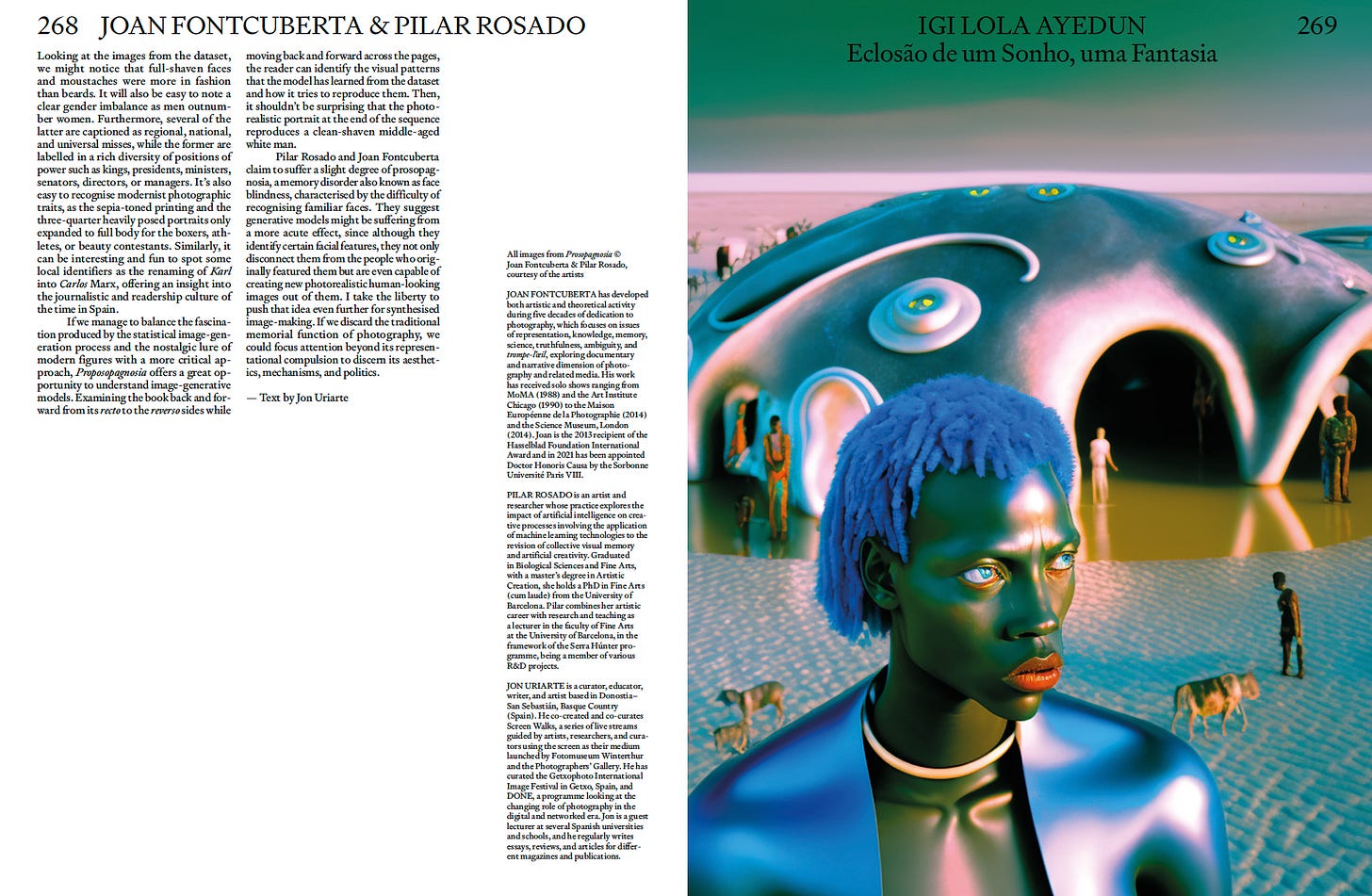

‘By researching the influence of African territories in technology, Ayedun travels the physical/spiritual paths that are present in the visual repertoire of the images she builds. She is less interested in a purely symbolic value; they can be as the way itself: insignias of the revelation of multiple times. This visual audacity that is amplified by the cultural capacity of the images is what evokes these visual spasms that are conducting us in a crossing by different points in time, always transubstantiating our own perception. An attempt of displacement, even if temporary, of the ways to describe form and matter.’ - Tarcisio Almeida

‘Mavropoulou started A Hollow Garden during the dragged-out months of the Covid-19 lockdown, where her life was split almost symmetrically in two: on one side, the extensive walks in the forests and hills around her house in the outskirts of Athens; on the other, the long hours in front of the different screens enabling all social, professional, and leisure duties and needs. Similarly to millions of others, the paradox of the dichotomy generated by a system of restrictions became clear to her: spending time outdoors or online were the two only possible options, and they seemed mutually exclusive. But are they really so? Or is there any prospect for a connection between technology and nature that doesn't merely imitate or counterfeit when not replacing altogether?’ - Paola Paleari

’To speak of artificial intelligence is to speak of archives and how we wish to imagine our digital commons to be curated, framed, and played by software. To subvert the more mainstream paths that AI companies take, we are seeing artists resort to creating their own algorithms, tools, and datasets. Allahyari has done extensive research for creating novel digital datasets on the Qājār dynasty, that impact the final result of the work itself. As any artistic tool shaping the aesthetic quality of the work, in the case of AI, the dataset becomes the material to ‘paint’ with.’ - Yasaman Sheri

4: From the studio

At Photo London I came across an image that caught my eye because of its strong resemblance to a photograph I took many years ago. From content, to lighting and perspective - undoubtedly a mirror image. At first I didn’t think much of it, as it is not uncommon for artistic styles and themes to resemble one another. However, on closer inspection I learned that it had been created by AI, which put things into a different perspective. I found myself pondering whether my own photographs are feeding AI’s, and that I might be looking at the artificial afterlife of my own photograph? I will never know, but it was a good impetus to consider where we place artworks online, and whether we can ever safeguard their authenticity. I’m still processing….

If you’ve read this far, thank you and hope you enjoyed! My next letter will reach you at midnight on June 8th. Until then, take care.

x

Looking forward to receiving my copy!! xx

I will try and check the magazine out, especially having just written about how AI-phobic I am: https://neilscott.substack.com/p/jerry-uelsmann